Author: admin

Zeitz Collection

In Collector’s Eye, Sayers Consultancy invites prominent collectors to select a favorite work of art in their collection and to explain why it speaks to them personally as well as aesthetically.

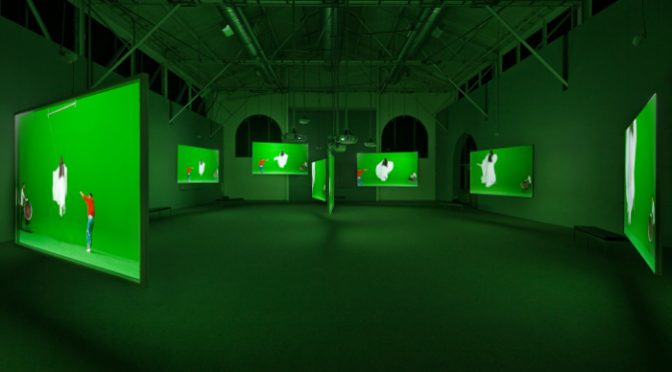

Here Jochen Zeitz talks about his enthusiasm for a work by Isaac Julien titled “Ten Thousand Waves” in the Zeitz Collection, now located in the new Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa (MOCAA) in Cape Town, South Africa.

Jochen Zeitz’s Choice and Comments

“While I was the CEO of PUMA, through our PUMA Creative programme, we sponsored Isaac Julien’s participation in the Sydney Biennale, where he inaugurated a nine-screen projection called Ten Thousand Waves. Later we sponsored the presentation of Ten Thousand Waves at the Bass Museum as part of Art Basel Miami Beach. After having seen this piece installed in various ways, I knew it should also become part of my collection.

Ten Thousand Waves confronts us with a powerful message that highlights one of the great challenges of our time: Movement of people by need or choice. Migration demonstrates humanity’s aspirations and dreams of a better life elsewhere, but also the positions of vulnerability that migrants often find themselves in.

The work deals with a group of Chinese migrants in the UK who are gathering shellfish on the beach, but are lost at sea as the rising tides trap them in the dark of night. It is a deeply moving visual metaphor contrasting the beauty of nature—its power to inspire—with its power to overwhelm and destroy.

This piece seems so relevant to me, as migration from China has happened all over the world, and now with the new waves of migration in Europe, the challenges affecting humankind are man-made.

I think it is telling that Isaac Julien’s heritage would have originally been Nigerian, his parents growing up on the West Indies, and then Julien himself living and working in London.”

Isaac Julien

Isaac Julien was born in 1960 in London, where he currently lives and works. While studying painting and fine art film at St Martin’s School of Art, from which he graduated in 1984, Isaac Julien co-founded Sankofa Film and Video Collective, in which he was active from 1983 to 1992. He was also a founding member of Normal Films in 1991.

He was nominated for the Turner Prize in 2001 for his films The Long Road to Mazatlán (1999), made in collaboration with Javier de Frutos, and Vagabondia (2000), choreographed by Javier de Frutos. Earlier works include Frantz Fanon: Black Skin, White Mask (1996), Young Soul Rebels (1991), which was awarded the Semaine de la Critique Prize at the Cannes Film Festival the same year, and the acclaimed poetic documentary Looking for Langston (1989), which also won several international awards.

Isaac Julien was Visiting Lecturer at Harvard University from 1998 to 2002 and a research fellow at Goldsmiths College, University of London from 2000 to 2005. He has also been a faculty member at the Whitney Museum of American Arts and Professor of Media Art at Staatliche Hoscschule fur Gestaltung, in Karlsruhe, Germany.

He has received numerous awards, including the Performa Award (2008), the prestigious MIT Eugene McDermott Award in the Arts (2001), and the Frameline Lifetime Achievement Award (2002), and the Grand Jury Prize at the Kunstfilm Biennale in Cologne (2003). His work Paradise Omeros was presented as part of Documenta XI in Kassel (2002). In 2008, he received a Special Teddy at the Berlin International Film Festival for the film Derek.

Isaac Julien has had solo shows at major museums in Europe, the United States, and South America. His film Ten Thousand Waves (2010) went on world tour and has been on display in over 15 countries so far, including at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 2013/14. Isaac Julien is represented in both public and private collections, including the Museum of Modern Art (New York), Tate Modern, Centre Pompidou, and the Guggenheim Collection.

Jochen Zeitz

Jochen Zeitz is an entrepreneur, business leader, dedicated environmentalist, innovator and globetrotter who at any moment might be found in Africa, the United States, Europe or elsewhere in the world. Born in Mannheim, Germany, he attended the European Business School rather than following a family tradition and becoming a doctor.

He began his career as a marketer at Colgate Palmolive. He then joined the footwear company Puma in 1990, where he led the transformation of the business into a global lifestyle brand. In 1993, he was appointed Chairman and CEO of PUMA, a position he held until 2011, when he decided to step back and focus on two issues to which he is very committed – environmentalism and corporate sustainability.

He became Chief Sustainability Officer of Puma’s parent company, Kering Group, in 2010, a role that complemented a personal initiative, the creation in 2008 of the Zeitz Foundation of Intercultural Ecosphere Safety, which supports innovative sustainability projects to balance conservation, community development, culture and commerce.

Jochen Zeitz’s love story with Africa dates back to his early 20s, when he first traveled to the continent. A decade ago, Jochen Zeitz purchased an old cattle farm on 50,000 acres of Kenyan grassland. It became Segera, an eco-retreat where African wildlife, including endangered species, could live on land protected by the Zeitz Foundation and the surrounding community.

The Zeitz Collection

The Zeitz Collection was founded by Jochen Zeitz in 2002. Initially, he collected American Pop Art, Americana manuscripts and Native American artifacts. In 2008, Jochen Zeitz met Mark Coetzee, and together they decided to build a collection of contemporary art from Africa and eventually open a major museum of contemporary African art in Africa. Since then, he has assembled one of the most representative collections of contemporary art from Africa and its Diaspora found anywhere. Now that collection is set to have an impressive home at the new Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa (Zeitz MOCAA).

The Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa (Zeitz MOCAA) is a public, not-for-profit cultural institution that focuses on collecting, preserving, researching, and exhibiting cutting-edge contemporary art from Africa and its Diaspora as well as developing and supporting educational and enrichment programs for all. It is the first major museum in Africa dedicated to contemporary art. Zeitz MOCAA will open in 2017 in the transformed heritage-listed Silo building, repurposed by Heatherwick Studio, in the Silo District of the V&A Waterfront in Cape Town. Mark Coetzee is the Executive Director and Chief Curator of Zeitz MOCAA.

For more information, please visit:

Picasso’s Discovery in 1907…

At the start of the twentieth century, artists in Europe discovered a new source of artistic inspiration from another continent – Africa. In 1906, André Derain visited the British Museum and was overwhelmed by the masks and figures he discovered there. He wrote to Matisse of his astonishment at their raw expressive power and of his realization that artists had a new form of representation to draw upon.

A sacred encounter.

Derain and Matisse, who saw these masks and sculptures not as curiosities, but as true works of art, passed along their enthusiasm to another artist – Pablo Picasso. Although stylistic echoes of African art appeared in Picasso’s work soon thereafter, it was only in the following year that a new encounter with these “sacred”; and “magical”; forms from Africa would fundamentally transform his artistic vision and his notion of himself as a painter.

In the spring of 1907, at Derain’s urging, Picasso visited the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro in Paris. In the following text from André Malraux’s Le Miroir des Limbes – II. La corde et les souris, Picasso describes in his letter to André Malraux his impressions and the revelation he had while looking at the works from Africa on display there.

Picasso’s letter to Malraux

“People often talk about the influence of African art on me. What can I say? We all liked fetishes. Van Gogh said, ‘We all had Japanese art in common.’ For us, it was the Africans. Their forms didn’t influence me more than they did Matisse. Or Derain. But for them, the masks were sculptures like any others. When Matisse showed me his first African head, he talked about Egyptian art.

“When I went to the Trocadéro, it was disgusting. Like the Flea Market. The odor. I was alone. I wanted to leave. But I didn’t. I stayed. I stayed. I understood that it was very important. Something was happening to me…

“The masks were not like other sculptures. Not at all. They were magical things. So why weren’t Egyptian or Chaldean sculptures magical? We didn’t realize: they were primitive, not magical. The African pieces were intercesseurs. Ever since then, I’ve known the word in French. They stood against everything, the whole; against the unknown, threatening spirits. I was always looking at fetishes. I understood; I too am against everything. I too believe that everything is unknown, that everything is an enemy! Everything as a whole! Not the details, women, children, animals, tobacco, playing, but everything together! I understood what the Africans used their sculpture for. Why sculpt like that and not some other way? After all, they were not Cubists! Cubism did not exist. It was clear that some fellows had invented the models, and others had imitated them. That’s tradition, isn’t it? But all the fetishes were for the same thing. They were weapons to help people avoid obeying the spirits so they could become free. Spirits, the unconscious – something that was not talked about much then – emotion: they were all the same thing. I understood why I was a painter.

“All alone in that dreadful museum, with the masks, the Redskin dolls, the dusty cloth figures. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon must have come to me that day, not at all because of the forms, but because it was to be my first exorcism painting!”

André Malraux, The Mirror of the Limbs – II. The Cord and the Mice, 1976.

Chen Dabing Chinese Love Affair With Africa

In this edition, Chen Dabing tells Sayers Consultancy about his involvement with Africa and African art. He also presents two of his favorite works in his collection: a sculpture by Beezy Bailey and a painting by Ayanda Mabulu.

Chen Dabing is an entrepreneur and the founder of the Chenshia group of companies. Born and raised in China, he first traveled to Africa in 1991. It was the beginning of a love story with South Africa and the African continent, its culture, and its people. An avid art collector and patron of the arts in both Africa and China, he is the founder of the Chenshia Museum in Wuhan, whose mission, in Dabing’s words, is to “collect and exhibit works of art to appreciate and respect, to preserve and protect, to promote and benefit, to share and prosper.” He is also a director and founding member of the Africa-China Friendship Association and Africa-China Entrepreneurs Forum.

Interview with Chen Dabing

1/ You were born in China. Could you tell us about the world you grew up in?

I was born and raised in the rural area of Xiangyang, in central China, where battles have been fought for the control of its strategic position throughout the 2,800 years of its existence. I grew up listening to all kinds of historical stories passed on by word of mouth from our elders. I never met my own grandfather, who was abducted by the nationalist government to fight a losing civil war against the communists. I knew who conspired and helped with his capture. My cousin and I used to take revenge against the perpetrator, an old lady, by throwing rubble into her house whenever we got jealous of kids being spoiled by their granddads. I kept dreaming he was alive and would come home for a long time in the early eighties, when the tension started to ease across Taiwan Strait, but it remained just a dream. In those days we were extremely poor, all with large families, all the same poverty, lacking minimal necessities, but we were endowed with the freshest air, purest water, and a simple, idyllic life under a constantly changing sky; cloudy or clear, we could see miles and miles away. I still remember drinking water directly from the streams or rice fields whenever we were thirsty. Then chemical fertilizer was introduced after the electric poles, and the subsequent economic reform and rapid development to catch up to the West in the last 30-odd years has made my ancestral home almost uninhabitable.

2/ You are an entrepreneur in multiple sectors. You set up a business in South Africa in 1991, and you say this company, Chenshia, is the result of your “love affair with Africa.” Could you tell us when and how this “love affair” began?

I worked for a State Owned Enterprise (SOE) in China for six and a half years before I quit and started on my own in March 1989 in the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone. Everything could be done there in special ways compared with the rest of China. Certain people there were encouraged to get rich first. After my brief stint in Shenzhen, I managed to get out of China in 1991. In those days it was still hard for Chinese citizens to travel overseas, not only due to the internal control, but also because of uneven immigration policies towards Chinese nationals. I traveled to Bangladesh and landed in the Seychelles, then the only country in the world that granted Chinese nationals a visa on arrival. I went on to visit Kenya, where I secured my visa for South Africa, a legendary country of diamonds, “a girl’s best friend,” as it had been referred to for many years in China, so far away yet so close to everyday life in the new dispensation of an emerging consumerism back in my motherland. Chenshia was subsequently created in South Africa. Its Chinese translation is “diamond.” When China introduced its trademark legislation, we had “Chenshia” and “diamond” registered as our trademarks. Today Chenshia still conducts its diamond and jewelry retail business in both South Africa and China, and we will soon offer our stones and jewelry products and services to high-net-worth individuals and investors on the ICBC online platform under the name South African Pavilion.

3/ What makes you feel strongly connected to South Africa? How do you explain this connection?

I touched down on African soil the first time in 1988 and immediately fell in love with its people, arts, culture, and history. I traveled for almost a month in Africa, from Ethiopia to Kenya and then to Nigeria, looking for business opportunities and partners for the SOE I was working for. At the end of the journey, I decided to quit the government job and move out of China to establish my own business. It was Africa that inspired me and opened her arms to me.

4/ When did you become interested in art? When did you start collecting? We know you collect African and Asian art, both traditional and contemporary. What did you collect at the beginning? How has your collecting evolved?

I was artistic at an early age and particularly liked to draw, but I was never encouraged to explore my artistic talent. Instead, I chose playing traditional Chinese musical instruments like the flute and Erhu as a pastime. In the summer of 1977 I had to give up all artistic pursuits to concentrate on exams that subsequently changed my life forever.

The first time I collected art was actually during my first trip to Africa. I was captivated by wooden sculptures that were so vivid, as if they were smiling and talking to me all the time. But I could only afford to buy a tiny old African female figure, which sat on my desk for a long time before someone helped himself or herself to it during my absence. I still miss her. I continued to collect historical artifacts and contemporary African art after I relocated to Africa. I started to collect Tibetan art in the late nineties. The story-telling religious themes painted in mineral pigments were so intriguing, intimidating yet so inspiring and so peaceful. The artistic achievements and craftsmanship of those ritual and ceremonial items demonstrated the highest spiritual enlightenment beyond monetary terms. I started to collect contemporary Chinese watercolors and prints at the end of the last century, especially paintings depicting the development and social changes before and after the Cultural Revolution. In recent years, I have tended to collect works by young artists in Africa and China, trying to make a little difference in their daily life and career development.

5/ Could you tell us about some of your favorite works in your collection?

I have a lot of favorites in my collection, but let me give you two typical examples.

One is titled, “As It Is In Heaven,” a work by Beezy Baily. He describes how Mark Read, a gallerist and chairman of the World Wild Life Fund, called him one morning to say that he had a skeleton of a black rhino. Its horn was now fake, but the bones were real. Mark asked him if he could do anything with it. He decided he had to do something that spoke to the plight of the rhinos and the devastating effect their potential extinction could have on humanity. So he made a multidimensional show of light, sound and a three-dimensional presence – an angel, wings, flying, a horn of pure gold – creating an uplifting experience loaded with tragic beauty, with Allegri’s “Miserere Mei, Deus” choral music singing of the spirit rising from the dead, of transcendence.

The second is a painting by Ayanda Mabulu titled “Death Was the Only Way Back to Innocence.” This powerful work is inspired by the death of his mother and is an homage to her. She and the artist are the central figures in the painting, with the body of his dead twin brother lying at their feet. They are surrounded by symbolic elements – a snake representing pain and illness, a watch the irreversible passage of time, a dog the guardian ancestors, the bandages around him and his brother the pain they have shared in life, and a bird the dying soul of their mother. It is a very moving depiction of the suffering they have experienced.

6/ As a great lover of South Africa and the arts, I know you are a strong supporter of African visual arts. Could you tell us about some actions you are taking to support African art? And about your involvement in Zeitz MOCAA.

We identify young and/or emerging artists from South Africa and the rest of the continent and send them to China on a residency or in other cultural exchange programs. We exhibit works they have done in their home country or new works created during the exchange in our private museum. And we invite Chinese art critics and media to review their works. These works are subsequently moved to commercial galleries to be promoted with Chinese collectors. Occasionally, their works are presented to the local auction house for further promotion.

I was invited by Mark Coetzee, now chief curator of Zeitz MOCCA, to his dinner at the first Cape Town Art Fair. I was deeply impressed by his professionalism and insights into the contemporary art world. It is a privilege to be associated with him and through him with Zeitz MOCCA, an exciting new museum destination in Africa, created more than 150 years after the Egyptian Museum.

7/ How did you decide to create the Scheryn Art Collectors Fund? Where does this name come from? Why is the temporary Zeitz MOCAA Pavilion named Scheryn?

I met my partner Herman Steyn sixteen years ago through our children, who went to the same school, and we are close neighbors. Herman runs a very successful financial services company with operations in China. I did not realize that Herman had become a seasoned and passionate art collector until early 2010. In one of our visits to China, where he was invited to visit my headquarters and private museum, we kept talking about art rather than business. We celebrated the end of our journey in a small Hutong, at a Peking duck restaurant named Liqun, which has been frequented for years by politicians like Al Gore, celebrities, and diplomats from all over the world. I go to this restaurant to entertain my family and friends in Beijing. I proposed to Herman that we set up an art collector’s fund specializing in contemporary African art by African artists on the continent and in the diaspora. Herman was delighted and agreed to start the process upon his return to Africa. We decided to celebrate the idea at the same restaurant every time we were in town. The first celebration at Liqun was with Zeitz MOCAA team during their China tour in 2015. Herman suggested the name Scheryn, and I searched on the Internet and found no other entities so named. I find it very unique. It sounds very close to the pronunciation of “new blood” in the Chinese language (新锐). Together we decided to donate a substantial amount to support Zeitz MOCAA in its early stage, and in return, the museum rewarded us with a Scheryn Pavilion in recognition of our support.

8/ You have created the Chenshia Museum in China. What is in the museum? What is your ambition for the museum? How do you choose what will be in your exhibition program?

In 2006, I purchased a prime riverfront property in downtown Wuhan, located in the middle reach of the Yangtze River. I came to the city to pursue my studies and career when I was 17 and left when I was 26. It has always had a very special place in my heart, and I decided to turn the property into a private museum to house and exhibit my permanent collections and to share the platform with artists, art critics and historians, art lover, supporters, and collectors. It has been open to the public for free since it opened in May 2010. It has become a prestigious name for the municipality as a favorite tourist destination. The former French Prime Minister Dominique de Villepin was given a private tour when he was in town. He particularly enjoyed our African and Tibetan collection.

In coming years, I would like to see Chenshia Museum develop sister relations not only with other private museums, but also public museums and art institutions, both in China and abroad. We have a professional team with degrees from fine arts institutes to manage the museum’s annual program day to day. We call on independent curators to select Chinese and international artists to exhibit at our museum. Artists from Africa, Asia, America, the UK, France, Georgia and other countries come and exhibit their works at our museum and interact with audiences, art critics and collectors. The local TV regularly broadcasts the events, interviews, and sometimes the panel discussions during these exhibitions.

9/ You are the director and founding member of the Africa-China Friendship Association and the Africa-China Entrepreneurs Forum. Could you tell us how you see Chinese-African relations in both the cultural and business spheres?

Chinese-African relations began in the early Ming Dynasty, and Chinese explorers came to Africa almost two hundred years earlier than their European counterparts. They came to survey the African continent, and it was included in the Da Ming Hun Yi Tu (World Atlas of Ming), circa 1389, on a 17-square-meter silk panel. The Chinese brought gifts like porcelain and farming tools as well as science books with illustrations of inventions and applications to Africa. The only thing they took back to China was a giraffe and a few other animals for the Chinese royal family. Chinese contact with Africa was reduced to a minimum after an inward-looking Ming emperor abruptly ended Chinese exploration. In the late nineteenth century, the Chinese came to South Africa to join their African brothers as indentured laborers to mine gold. They were mistreated and denied integration and citizenship. They were repatriated to China in the early twentieth century. In the 1960s, the relationship gradually warmed when African countries gained their independence from their Western colonial masters. China, which was then still recovering from the war with Japan and the subsequent civil war that almost ruined the country and depleted its economy, came to Africa’s aid in all possible ways. When I travel through Africa, I can still see clinics, hospitals, schools, stadiums, motorways, railways and government buildings designed, constructed and operated by the Chinese people. Farming skills were transferred, and medical teams treated the sick and attended the injured.

Business relations with Africa only picked up early this century when China experienced an economic boom that required resources from Africa to sustain its development. But most of the resources were already controlled by Western multinationals, leaving China no alternative but to purchase at a premium from these companies, while investing heavily in new, uncharted territories that are extremely difficult and capital-intensive and that are normally shunned by Western businesses. However, most of the Chinese investors are making a long-term commitment to Africa. Most of the infrastructure projects being financed and built by Chinese companies throughout Africa are genuinely intended to benefit the African people and ensure their sustainable development.

Culturally, the African and the Chinese peoples have a lot in common. For instance, the traditional family structures; relationships and the management of core and extended family members and relatives; respect for elders as well as social networking in rural and communal contexts. I find it quite natural that Africans and Chinese bond with each other. So it is not surprising at all to witness a tremendous and steady increase in exchange programs. There are about 800,000 to 1,000,000 Africans currently living and working in Guangzhou alone, while close to a million Chinese people live and work permanently across the African continent, with intermarriage on the rise. The number of Africans seeking higher education in China has become phenomenal in recent years, and they are finding jobs back home in Chinese companies or starting their own businesses trading with China. We are living in an exciting time to experience and witness how Africa and China are deepening their mutual trust and continuing the development of people-to-people relations and cultural ties. The aspirations of the African renaissance coincide with those of the Chinese dream. The FOCAC held last December in Johannesburg has ushered in a completely new chapter in China–Africa relations, and many good stories are just beginning to unfold.

10/ How would you like to see the relationship between China and South Africa develop? What role do you feel you can play?

I personally believe the relationship between China and South Africa will always be a dominant and determining factor in China–Africa relations, since both countries are playing an important role and working closely with each other at BRICS and other international organizations. China has become the world’s second-biggest economy, and it will serve as an engine to get the world economy out of the current slowdown and back into full swing, while South Africa is a powerhouse and a beacon for the rest of Africa. It serves as a gateway for Chinese business development in southern and sub-Saharan Africa. South Africa is rich in resources that China needs to maintain its economy’s healthy and sustainable growth, while China offers a massive market not only for South African minerals, but also for its agricultural produce. Chenshia Green, a consortium formed with a multinational of local origin, has recently started to export South African fruits directly to Shanghai. The time has come for South Africa to overhaul, upgrade and/or replace its infrastructure and industry, but its wings are clipped by its current balance sheet. However, China is well positioned to offer both financial and technical solutions. As an entrepreneur, my role is to identify and tap the opportunities existing in the aforementioned process and take advantage of my personal experience, expertise, networks and connections to maximize benefits for both countries.

11/ Many people compare the growing interest in African art with what happened a decade ago with the Chinese art scene. Do you think this comparison is appropriate?

Yes, I honestly share the same view and strongly believe that it is now Africa’s turn on all fronts. Africans are born musicians and artists, and they are so natural and so creative that they inspire everyone who encounters their arts and culture, like Picasso in the West and Luo Zhongli in the East. That same belief led us to establish Scheryn, and we are finalizing the details to promote our fund to the Chinese investors who are getting more and more interested in buying contemporary African art.

12/ You are a passionate collector of historical artefacts. Is there an interest in China in artefacts from Africa? Are you encouraging that interest? You also collect contemporary African art. Is there also an interest in it in China? What trends do you see that you think are important in these art markets?

There has always been an interest in traditional African art, and with the arrival of more and more Chinese people, sales have been picking up in recent years. Chenshia Group has been exporting traditional African art to China for a few years. At first it was for our retail window dressing, but then customers insisted on buying it. There are not many Chinese collectors who know about or understand the importance of contemporary African art, but I know a bunch of executives working in or traveling frequently to Africa who have started buying from local galleries. I also know some senior Chinese diplomats who have acquired some interesting pieces during their posting in Africa. These people are unintentionally promoting contemporary African art. Once Chinese collectors are exposed, educated and professionally guided, I see no reason why African art shouldn’t make an impact among Chinese collectors and investors. My organization is dedicated to promoting African art in China on a long-term basis.

13/ Are you involved in any charitable activities in South Africa?

I have been elected vice president of the South Africa Soong Ching Ling Foundation, which is the only charitable organization in Africa officially registered in the name of the First Lady of China. Since its establishment in 2009, the foundation has urged the local Chinese community to regularly donate funds to assist orphans, and on June 1, 2015, we delivered a newly built orphanage named China House. We intend to replicate this successful social responsibility model in other parts of Africa.

14/ You have accomplished many things in many different fields. The Motto of Chenshia, the Group you founded is “Capture the moment, invest in dreams, inspire individuals and share the future.” What haven’t you done yet that you really dream of achieving?

In terms of business development, I always look at Africa as one country and always compare it to China in a lot of different ways. We have 34 provinces and 1.3 billion people in China, while Africa has 54 independent countries and 1 billion people. The numbers do matter. To help enrich so many people, there exist unlimited opportunities and challenges. I have been dreaming of developing a life insurance company with a wide range of products and services to have all Africans covered from cradle to grave. I have been dreaming of establishing a chain of hospitals in Africa where Chinese medical graduates must come to work for one or two years as part of their volunteer or internship program to help Africans in need of medical treatment at an affordable cost. I have many other African dreams, but I have to formulate and realize them step by step.

Artbeat Today

California Dreaming? Now It’s A Reality For Contemporary Art (1/24/2017) MarketBeat - Has the West Coast become a top destination for contemporary art? It certainly looks that way. In Los Angeles, there’s ...

California Dreaming? Now It’s A Reality For Contemporary Art (1/24/2017) MarketBeat - Has the West Coast become a top destination for contemporary art? It certainly looks that way. In Los Angeles, there’s ... Finding the Sense of Art in Life After January 20th 20 January, 2017 Voices in Art - John Berger, in 1960: "It is our century, which is pre-eminently the century of men throughout the world claiming the ...

Finding the Sense of Art in Life After January 20th 20 January, 2017 Voices in Art - John Berger, in 1960: "It is our century, which is pre-eminently the century of men throughout the world claiming the ... Zeitz Collection (11/17/2016) Collector's Eye - In Collector’s Eye, Sayers Consultancy invites prominent collectors to select a favorite work of art in their collection and to ...

Zeitz Collection (11/17/2016) Collector's Eye - In Collector’s Eye, Sayers Consultancy invites prominent collectors to select a favorite work of art in their collection and to ... Black Mountain College (1/10/2017) Looking Back - Black Mountain College was a small, experimental liberal arts college founded in 1933 in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North ...

Black Mountain College (1/10/2017) Looking Back - Black Mountain College was a small, experimental liberal arts college founded in 1933 in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North ...