The Liberating Spirit of Robert Rauschenberg

“Art is an experience designed to allow every individual to be and find themselves.” – Robert Rauschenberg.

Leading up to the sweeping Rauschenberg retrospective that opened at Tate Modern on December 1 was another look back at the artist with a major exhibition at the Ullens Centre for Contemporary Art (UCCA) in Beijing last summer. Rauschenberg in China centered on a single work, “The ¼ Mile or 2 Furlong Piece,” which had not been shown since 1999. Some 300 meters long (the distance between the artist’s home and his studio on Captiva Island, Florida), it consisted of 190 two- and three-dimensional pieces installed chronologically on walls that zigzagged through the UCCA’s Great Hall.

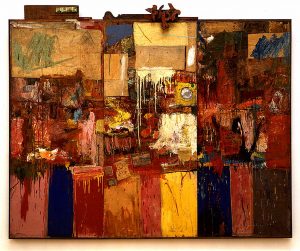

This series of works produced between 1981 and 1998, a “Combine” of sorts that dwarfs (at least in size) the groundbreaking Combines created early in his career, has been dubbed a “self-contained retrospective.” This display of the artist’s protean creativity of course includes pieces in which he worked “in that gap between art and life” he famously spoke of, incorporating objects from the real world in his paintings to produce jarring yet aesthetically compelling compositions. At the same time, the disparate elements of “The ¼ Mile” chronicle a reality of their own, the evolution of Rauschenberg’s ever-evolving and multifarious art.

The show at UCCA reveals another aspect of Rauschenberg’s urge to bring things together, too. He began “The ¼ Mile” the year before making his first trip to China. His experience during that trip, coupled with his belief that culture was a medium for uniting people and promoting understanding and peace, led to the Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange (ROCI) project, a self-funded initiative in which he created and installed exhibitions of his work successively in ten countries (Mexico, Chile, Venezuela, China, Tibet, Japan, Cuba, USSR, Malaysia and Germany) between 1984 and 1991.

The ROCI China exhibition in Beijing, held in 1985, attracted some 300,000 visitors and had a profound impact on the development of modern art in China and the so-called ’85 New Wave art movement there.

The notion of “permission,” of his having a “liberating effect” on artists, is often mentioned in relation to Rauschenberg. There can be little doubt that what artists discovered in these exhibitions and Rauschenberg’s openness and interaction with them gave them “permission” not only to combine different media in their work, but also to follow their own creative impulses, while encouraging their fellow artists to do the same.

Rauschenberg and Black Mountain College.

Openness, interaction and mutual encouragement are things Rauschenberg himself found in a unique setting as he sought his direction as an artist. After studying briefly at the Kansas City Art Institute and the Académie Julien in Paris, he enrolled in 1948 at Black Mountain College, in North Carolina (see the “Looking Back” section).

A progressive school whose faculty included many of America’s foremost visual artists, composers, poets and designers, Black Mountain College was founded on an interdisciplinary approach to education that gave equal attention to painting, weaving, sculpture, pottery, poetry, music, and dance. Rauschenberg’s teacher there was the German-born artist and educator Josef Albers, who believed that learning called for direct interaction with life and familiarity with the physical properties of the material world. He also encouraged his students to work with a wide variety of materials.

Albers imposed strict discipline in the classroom, and Rauschenberg described Albers as influencing him to do “exactly the reverse” of what he was being taught. He may have chafed at Albers’ strict pedagogy, but his mentor’s emphasis on the importance of materiality in the creative process and of keeping art rooted in the real world seems bound to have resonated with Rauschenberg’s sensibility, intuition, and instincts.

And though lack of confidence is not something usually associated with Rauschenberg, it may have emboldened him to adopt the vocabulary that defined his work in the future – collages of images from magazines and newspapers, photographs, clothing, textiles, objects, cardboard, scrap metal – ordinary stuff of everyday life that he brought together in radically innovative ways from the 1950s onwards.

Rauschenberg’s longstanding friendship with composer John Cage and choreographer Merce Cunningham, both of whom taught at the school and shared his desire to integrate daily life into art, also goes back to the Black Mountain period. Rauschenberg has said that Cage had a “fantastic influence” on this thinking. “He gave me permission to go on thinking…he was the only one who gave me permission to continue my own thoughts.”

Those times spent in a remote corner of North Carolina, in a community of artists and an environment that fostered interaction, experimentation, and a spirited exchange of ideas, were critical to the future development of his art and of contemporary art in general. It was the kind of liberating experience – the “permission given” to follow their own ideas, wherever they might lead – that other artists have described in speaking about Rauschenberg’s influence on them in the following decades.

The current retrospective at Tate Modern, presenting works from his days at Black Mountain until his death in 2008, will run until 2 April. It will then travel to the Museum of Modern Art in New York (21 May–Sept. 17, 2017) and later to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.